Research finds that ocean-dwelling fish entered freshwater environments on several occasions, evolving enhanced hearing abilities in the process.

When ancient marine fish transitioned from saltwater to freshwater environments, many also developed more complex hearing systems, including middle ear bones that resemble those found in humans.

About two-thirds of all freshwater fish , more than 10,000 species, ranging from catfish to aquarium favorites such as tetras and zebrafish — possess this specialized middle ear structure known as the Weberian apparatus. This system enables them to detect much higher-frequency sounds than most ocean-dwelling fish, with a hearing range similar to that of humans.

From ocean ancestors to freshwater innovators

Fish with a Weberian ear system, known as otophysan fish, were previously believed to have entered freshwater habitats around 180 million years ago, before the supercontinent Pangea began to fragment. However, Liu’s new analysis places their emergence later — roughly 154 million years ago, during the late Jurassic Period — after Pangea had started to break apart and modern oceans were beginning to form.

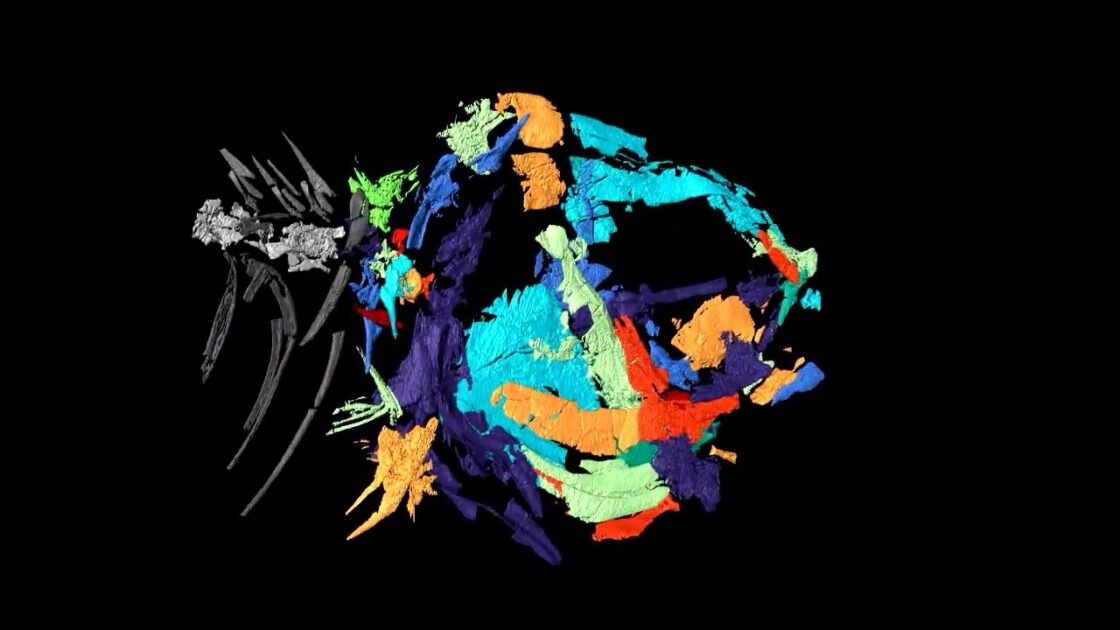

This simulation shows the amplitude and vibrations of zebrafish ossicles at a frequency of 1,012 Hertz. The large, triangular ossicle is called the tripus and is a modification of the rib and third vertebra to amplify sound vibrations from the air bladder.

By combining fossil evidence with genomic data, Liu determined that the early versions of these hearing structures first appeared in marine species. It was only after two separate lineages moved into freshwater environments that the Weberian apparatus became fully functional. One lineage gave rise to modern catfish, knife fish, and African and South American tetras, while the other led to carps, suckers, minnows, and zebrafish — the largest order of freshwater fish alive today.