Mars-like shock and chemical stress reveal ribonucleoprotein condensates as a key survival mechanism in yeast.

Life on Mars, whether in the distant past, today, or in the future, would face a range of severe environmental challenges. These include shock waves generated by meteorite impacts and the presence of perchlorates in the soil—highly oxidizing salts that disrupt hydrogen bonds and interfere with hydrophobic interactions.

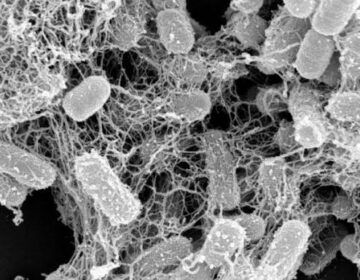

To examine how living cells respond to such stresses, Purusharth I. Rajyaguru and colleagues conducted experiments using Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a yeast species widely used as a model organism. The researchers selected yeast partly because it has already been examined in previous space-related studies.

Across many forms of life, including yeast and humans, cellular stress triggers the formation of ribonucleoprotein (RNP) condensates. These RNA and protein-based structures help protect RNA molecules and influence how messenger RNAs are processed and used. Once stressful conditions subside, the RNP condensates, including those known as stress granules and P-bodies, break apart.

Simulating Martian extremes in the laboratory

To recreate Mars-like conditions, the team generated artificial shock waves using the High-Intensity Shock Tube for Astrochemistry (HISTA) at the Physical Research Laboratory in Ahmedabad, India. Yeast exposed to shock waves reaching 5.6 Mach survived but showed reduced growth, and similar survival was observed in yeast treated with 100 mM sodium salt of perchlorate (NaClO4), a level comparable to concentrations found in Martian soils.