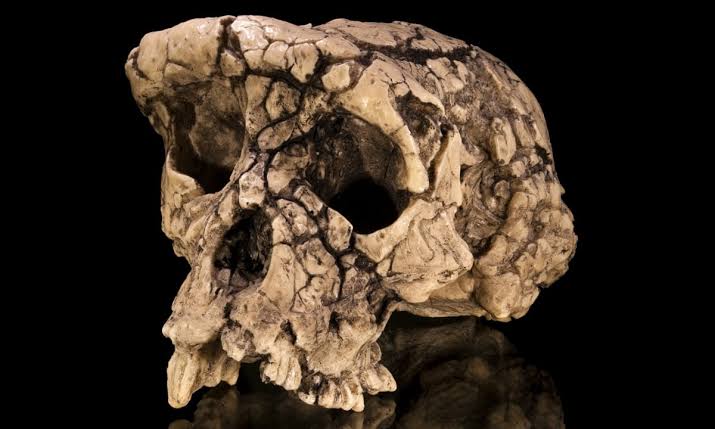

A seven-million-year-old fossil may mark the moment our ancestors first stood up and walked.

For years, scientists have argued over whether a fossil dating back about seven million years was capable of walking upright. That question matters because bipedal movement would place the fossil among the very earliest human ancestors. A new study by a team of anthropologists now presents strong evidence that Sahelanthropus tchadensis, a species first identified in the early 2000s, did in fact move on two legs. The conclusion is based on the discovery of a specific anatomical feature that until now has only been seen in bipedal hominins.

By combining 3D imaging with other analytical tools, the researchers identified a femoral tubercle in Sahelanthropus. This structure marks the attachment point for the iliofemoral ligament, the largest and strongest ligament in the human body and a crucial component for maintaining an upright posture while walking. The study also confirmed several additional skeletal traits in Sahelanthropus that are commonly associated with bipedal movement.

“Sahelanthropus tchadensis was essentially a bipedal ape that possessed a chimpanzee-sized brain and likely spent a significant portion of its time in trees, foraging and seeking safety,” says Scott Williams, an associate professor in New York University’s Department of Anthropology who led the research. “Despite its superficial appearance, Sahelanthropus was adapted to using bipedal posture and movement on the ground.”