A research team has uncovered an extraordinary Early Bronze Age ritual landscape at Murayghat in Jordan, offering valuable insights into how ancient communities adapted to social and environmental changes.

How did ancient societies react when their familiar world fell apart? Archaeological work at Murayghat, a 5,500-year-old Early Bronze Age site in Jordan excavated by researchers from the University of Copenhagen, may offer important clues.

Murayghat developed following the decline of the Chalcolithic culture (ca. 4500–3500 BCE), a time distinguished by thriving domestic communities, elaborate symbolic traditions, copper tools, and small religious shrines.

Shifts in climate and widespread social instability likely contributed to the collapse of this earlier culture. In the aftermath, communities of the Early Bronze Age appear to have responded by developing new ways to express their beliefs through ritual and ceremony.

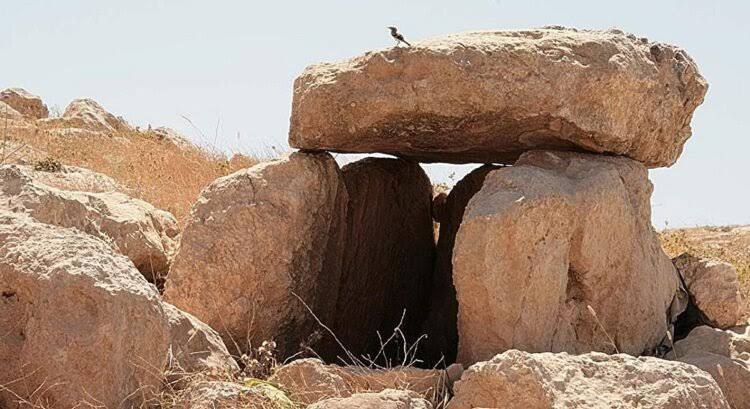

“Instead of the large domestic settlements with smaller shrines established during the Chalcolithic, our excavations at Early Bronze Age Murayghat show clusters of dolmens (stone burial monuments), standing stones, and large megalithic structures that point to ritual gatherings and communal burials rather than living quarters,” says project leader and archaeologist Susanne Kerner from the University of Copenhagen.

Redefinition of territory and social roles

More than 95 dolmen remains have been documented by the archaeologists, and the central hilltop of the site contains stone-built enclosures and carved bedrock features that also suggest ceremonial use.

These visible markers may have helped redefine identity, territory, and social roles in a time without strong central authority, Susanne Kerner points out:

“Murayghat gives us, we believe, fascinating new insights into how early societies coped with disruption by building monuments, redefining social roles, and creating new forms of community.”

Excavations at Murayghat have revealed Early Bronze Age pottery, large communal bowls, grinding stones, flint tools, animal horn cores, and a few copper objects — all pointing to ritual activity and possible feasting. The site’s layout and visibility also suggest it served as a meeting point for different groups in the region.