Diabetes mellitus commonly recognized as type 1 and type 2 diabetes—often dominates discussions due to its growing global impact and its links to lifestyle and autoimmune factors.

LlYet another, far less known form, diabetes insipidus, quietly affects hundreds of thousands of people worldwide. Despite sharing part of its name, this condition is entirely distinct from diabetes mellitus and has nothing to do with blood sugar regulation.

The term “diabetes” originates from the ancient Greek word meaning “to pass through,” aptly describing the frequent urination that characterizes both conditions.

In the more familiar diabetes mellitus, glucose accumulates in the bloodstream when the body either fails to produce sufficient insulin or cannot use it effectively. As a result, excess sugar spills into the urine, drawing water from the body along with it.

Those with diabetes often notice that they urinate more frequently and in larger quantities than normal. In some cases, the urine may even have a sweet scent. According to legend, Hippocrates the “father of medicine” once diagnosed diabetes by tasting a patient’s urine. Fortunately, modern medicine relies on test strips rather than taste to make this determination.

Diabetes insipidus is very different from diabetes mellitus. It has nothing to do with blood sugar. Instead, the problem is with a hormone called arginine vasopressin (AVP), also known as anti-diuretic hormone (ADH), which normally helps the body control how much water it keeps or loses.

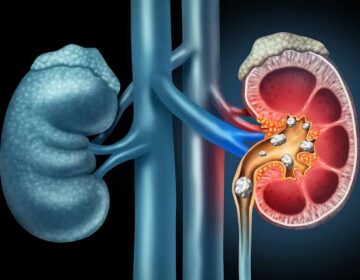

This chemical messenger, produced by the pituitary gland at the base of your skull, acts like your body’s water conservation system. When you need to hold on to fluid – say, when you’re dehydrated – AVP tells your kidneys to reabsorb water rather than letting it escape in urine.

When this system breaks down, the results are dramatic. Without enough AVP, or when the hormone fails to function properly, your kidneys lose their ability to conserve water. No matter how much you drink, you remain perpetually thirsty and dehydrated, producing large volumes of pale, diluted urine. It’s a frustrating cycle that affects around 2,000 to 3,000 people in the UK alone.